Subject: Draft of Remarks by Frederik L. Schodt (actual speech edited/improvised)

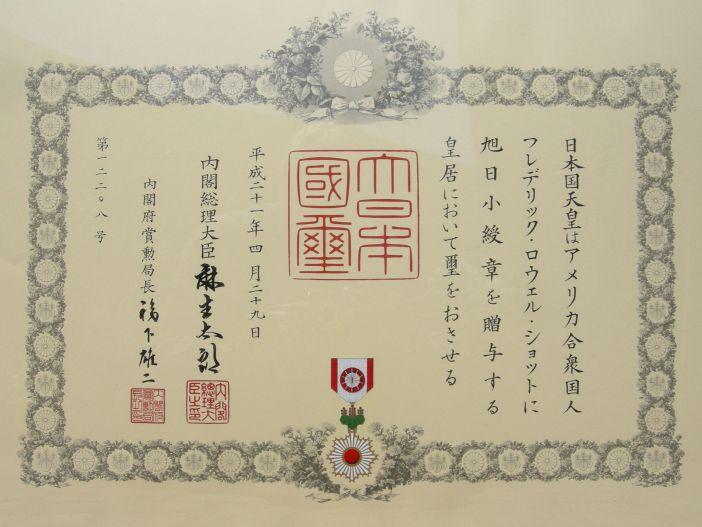

Occasion: The June 26th, 2009 Conferment Ceremony for the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette (旭日小綬章)

Location: Consul General of Japan’s Residence, San Francisco, California

First of all, I would like to thank the Government of Japan and Consul General Nagamine for this extraordinary honor. Also, my family, including my lovely wife Fiammetta, my honorary son, Mikey, and my nephew, Chris, who are all here today. And all my extended family, and all my friends in both Japan and America, many of whom are here now, who have supported me in so many different ways.

A couple of months ago, I received a call from Consul General Nagamine, telling me that I had been selected for this award, for helping to promote popular culture. He asked me if I would accept. And at that moment, a series of thoughts went through my head:

- First, I didn’t know they were giving out awards for contributing to (!) popular culture.

- Second, I wondered, Have I really done enough to merit such an award? After all, so many others (many of whom are here today) have probably done as much or more than I have.

- Third, and finally, I thought one only received such awards near the end of the line, and I’m only fifty-nine.

But all this took place in about one nanosecond. Almost as fast as I could, I told the Consul General, “I accept.”

It was suggested that I speak briefly today about Japanese popular culture, my background, and some of the changes I have seen, so I thought that I would do so. It is dangerous to ask a writer to be brief, but I will try, and skip around quite a bit, because I know that many people are hungry for the beautiful view and food here.

I first went to Japan when I was 15, in 1965, after having lived in Norway and Australia for many years. I left San Francisco, sailing under the Golden Gate bridge on the USS President Wilson, and I have been going back and forth ever since.

When I was twenty, I returned to Tokyo on a junior year abroad program from UC Santa Barbara, where I was an Asian Studies major, and I began studying Japanese intensively at International Christian University, or I.C.U. Both Jared Cook and Phil Gotanda, who are also here today, were studying there, too. I lived in a dormitory, and I noticed that my Japanese roommates were reading manga—huge, phonebook-sized magazines—instead of reading text books. It was a time when manga were becoming a symbol of youth culture, and university students in Japan were starting to proudly read them. It looked like great fun, so I began reading them, too. I fell in love with many popular manga works, especially Osamu Tezuka’s Hi no Tori, or Phoenix. So much of the literature in English about Japan in those days seemed to focus on kata no bunka, the form of Japan, on high arts, high literature, on zen, etc., but I was always more attracted to what seemed to me to be a very vibrant and sometimes low-brow popular culture. I loved the sense of humor and emotion in manga, and the wit that they showed Japanese people had. I thought that it would be great fun to someday do something related to manga, perhaps to translate them or write about them. But I had never heard of anyone doing so and had no idea how to start doing so.

In 1975, while living in Los Angeles, I received a Ministry of Education scholarship to study translation and interpreting at ICU, and as a result I was able to return to Japan and read many, many more manga. After my study program, I began working at a company in Tokyo called Simul International, translating often-boring government and commercial documents. Jared was also studying at ICU then as a post-graduate, and he and an ICU friend named Shinji Sakamoto came up with the idea of creating a group to translate manga. With another student, Midori Ueda, we formed a group called Dadakai (駄々会). The idea was to translate manga into English, and let the world know how wonderful manga are.

In 1977, we aimed for the stars and boldly made an appointment to visit Tezuka Productions, to see if we could get permission to translate the Phoenix. As I recall, when we arrived we first met Tezuka’s manager, Takayuki Matsutani-san (who is here today), and he looked very sleepy. As I would realize later, everyone who worked for Tezuka in those days tended to look rather tired and sleepy, because Tezuka kept such insane hours. To our great surprise, however, during our visit we also met none other than Osamu Tezuka, himself. In Japan he was already known as the manga no kamisama, or “god of comics.” He was very friendly, and gave us permission to translate his work.

We had no idea how to really translate manga properly in those days, but we used “white-out” to erase the Japanese in the word balloons and the sound effects, and then painstakingly wrote in the English by hand. We translated the first five volumes of Tezuka’s Phoenix, but we were terribly naive, and had no idea how to get these things published in America, because they were still “backwards,” and had to be read from right to left, instead of left to right. As a result, the manuscripts would languish in a safe in Tezuka Productions for nearly twenty-five years, collecting dust, until they were finally published a few years ago by Viz in San Francisco. We also translated other manga at the time, but like the Phoenix we could not get them published. Dadakai itself was short-lived. Jared and I, however, kept our interest in manga.

Around 1978 there was a group of American and Japanese volunteers working in Tokyo under the name of Project Gen. They were translating a long, semi-autobiographical work by Keiji Nakazawa, called Barefoot Gen, about the bombing of Hiroshima. It was part of a peace movement and the anti-nuclear campaign of the time, and it was not a commercial effort, but the group was able to solicit enough donations to get the first volume of the multi-volume series printed, in Japan. As far as I know, this was the first Japanese manga ever published in English, but it was actually printed and published in Japan, and sent to the U.S. and distributed largely through the help of volunteer organizations and church groups. The English in the word balloons had been written in by hand, and the panels rearranged on the page so that the book could be read from left to right, American style. Because it was a long series, in the interest of time, Project Gen members Alan Gleason and Masahiro Oshima-san asked Jared and I to translate the second volume. This became the first manga we translated that was actually published. In retrospect, it seems very appropriate that the first manga published in English had a peace theme.

In 1978 I returned to San Francisco and began working as a free-lance interpreter/translator/writer. I was still very much in love with manga, but I realized that it was way too early to publish manga commercially in English in the United States. It therefore occurred to me that writing a book about manga, and about Japanese popular culture, might be a good thing to do as a first step. Encouraged by my friend Peter Goodman, who became an editor at Kodansha International, around 1980 I started researching and writing. I also translated some segments of manga that would be included in the back of the book, and I hand-lettered and flopped the pages so that Americans could read them in the way they were accustomed to, from left-to-right.

It was a very different world then. In fact, I can still remember, in the late seventies, hearing warnings from the U.S. government against eating raw fish. When book was done, Peter and I had a conversation on the phone about the title. I wanted it to be “Japanese Comics, A New Visual Culture.” He wanted to call use the Japanese word manga. I was afraid, however, that people would confuse this with the Italian word to eat, mangia, or that it would be filed in card catalogs under the word “manganese.” Peter won out, and we settled on the title of Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. The other day, I’m pleased to report, I checked the latest edition of the Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam Webster, and both “manga” and “anime” are now of course included.

In 1981, a friend of mine in San Francisco, Leonard Rifas, had a small company called Educomics, and he was fascinated by Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen. Encouraged by Alan Gleason, he decided to publish it in America. To make it more accessible to an American audience, he repackaged the work in slim American comic book style, and retitled it Gen of Hiroshima. He broke the long work into smaller segments, rearranged the panels on the page, and professionally lettered it. Except for the fact that it was all black and white, it could be read just like an American comic book. The main problem was that it didn’t sell well, and would have taken forever to publish the entire series, which consisted of thousands of pages. It was a commercial failure, but became, as far as I know, the first Japanese manga to be translated, printed, and published in the United States.

Leonard will probably never forgive me, because in 1982, along with Alan Gleason I strongly encouraged him to publish I Saw It, a short, concluding story by Keiji Nakazawa—an autobiographical work with the same theme as Barefoot Gen. We thought that this would be more marketable in America, possibly a huge success. To make it more acceptable to Americans, the panels were not only rearranged and flopped, but colorized. To an American, I Saw It probably looks just like an American comic book. But this cost money, sales were less than stellar, and as far as I know Leonard still has a garage full of them.

Sometime in the mid-1980s, a man named Seiji Horibuchi came to visit me and ask my opinion of publishing manga in English in America on a commercial basis. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I know it wasn’t optimistic. I think I said that it was a great idea, but to forget about making any money, and good luck. Sure enough, along with his friend Satoru Fujii, he went on to form Viz in San Francisco for the Japanese publisher Shogakukan, and today I believe Viz is the largest publisher in North America of Japanese manga. They’re down on Bay Street in the old North Point Theater now, with over a hundred employees and sales of millions of dollars and they occasionally hire me to do work for them. Not too long after that, I met a young Canadian immigrant from the United States named Toren Smith. I thought he was just another enthusiastic fan, of whom there were more and more, but after working for Viz for a while he formed Studio Proteus, which packaged and translated Japanese manga into an American format, and today the work of Studio Proteus has been absorbed into Dark Horse Comics, in Oregon, which is one of the other largest manga publishers in America.

In 1988 Marvel Comics, one of the largest American comic book pubishers, also published Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, which, supported by an animated feature, was very popular. The idea in those days, though, was still to replicate as much as possible the “look” of American comic books—to make the books short, make sure they could be read from left to right. In the case of Akira, the work was also colorized, but the result was a degradation of Otomo’s lovely black and white drawings. The pages were so dark that they were hard to read. And that was one of the last major attempts to colorize Japanese manga.

With the explosion in video tape recorders in the late ‘eighties and ‘nineties, both anime and manga really took off. More and more companies appeared, publishing manga, such as Marvel Comics in New York and Tokyo Pop in Los Angeles. Even major American book publishers, such as Del Rey, eventually jumped into the market. And an interesting thing started to happen. The audience for manga started to really expand, beyond a core audience of young males, to include children and, increasingly girls. At conventions for manga and anime fans in America, we started to see more and more girls in Sailor Moon outfits, and some beefy forty-year-old men, too.

In 1994, a relatively unknown company called Blast Books published an relatively unknown underground manga called Panorama of Hell, by a relatively unknown Japanese manga artist named Hideshi Hino. This is not a notable manga book, but for a variety of reasons the publisher decided not to flop the pages. In other words, Blast Books let the American readers read from right to left, instead of left to right, or to read the books backwards. Amazingly, American fans had no problem with this. Other publishers also starting trying this, and it worked amazingly well. And it was cheaper. And it made Japanese artists, who had always hated having their art work flopped, very happy. That it may eventually slow the spread of manga into the mainstream market is something that publishers quickly learned to ignore.

Today, the vast majority of manga are not flopped. American fans are reading manga—not in American comic book style, but in true manga style. They read “backwards,” turning pages from right to left, and reading the panels on the pages in Japanese order. But they read the words in the panels in English order, from left to right. For hard core manga fans, the preference is also to not have sound effects translated, to leave Japanese written sound effects like dokan or gassha or dossu in the original Japanese, as part of the art work. To these hard core manga fans, the closer a translated book is to the Japanese original, the better, as long as they don’t have to learn Japanese. Of course, what many fans do not realize is that they are actually reading a hybrid creation, for Japanese do not turn pages or read panels in one direction, and then read the text in the speech balloons in another direction. In other words, most manga published in American today are really neither American comic books, nor pure Japanese manga, but something quite new, a hybrid.

Let me give you an example of how attached modern American fans are to the purity of the works they read. Jared and I have recently been translating a work for Viz called Pluto, by Naoki Urasawa, based on a single episode of Tezuka’s Astro Boy manga. The English language version of Pluto was recently reviewed on a web site, and the reviewer, thank god, loved the work. What fascinated me, though, is that he included a reservation, or mild complaint, about the fact that we did not leave in the Japanese honorifics. “While the English adaptation does not have any honorifics,” he wrote, “it is worth noting that the story so far takes place in German-speaking parts of Europe -- going without honorifics is arguably the more authentic option.” In other words, truly hard core fans would now like to have Japanese honorific words such as “sensei,” “sama,” and “san” left in, in Japanese.

Manga are a huge business today In America, and anime are even bigger. But the situation is not all roses. It has recently been tempting on the part of many of Japan's publishers and even the government to think that manga and anime have conquered the world, and that they may be a great way to earn foreign capital, perhaps even to replace income from declining manufacturing industries. In the last few years, however, it has become apparent that there is (or was) a bubble in the markets for manga and anime. Sales have plummeted in both Japan and the United States. In Japan last month, I also noticed that almost no one reads manga, or magazines or newspapers or books, for that matter, on the trains any more. Cel phones and games and other formats are slowly taking over. The change has been so dramatic that I sometimes even wonder if the American discovery of manga and anime is not a bit like the West’s discovery of wood block prints, geisha, and Japanese business management techniques—a discovery that takes place just as the object of infatuation is starting to disappear in Japan.

Manga and anime, like music and film and all entertainment media, are currently undergoing a radical change. In the age of Internet Protocols, when nearly all information is slowly migrating to the World Wide Web, we do not know what new formats manga and anime will morph into. But even if the sales volume and profits from current formats plummet, manga and anime will not disappear, and they will remain fascinating Japanese entertainment art forms. And they have already contributed to a global mind-meld that is occurring around the world in popular culture.

In 1983, when my book, Manga! Manga! was published, Osamu Tezuka agreed to write the Foreword. It was a huge honor for me. And it is fascinating today to go back and read what he wrote, and to see how prescient he was. He realized that Japanese animation, which did not have the same format problems as manga and could be more easily enjoyed, was actually opening the doors for manga around the world. “Having solved the problem of language, animation, with its broad appeal, has in fact become Japan’s supreme goodwill ambassador, not just in the West but in the Middle East and Africa, in South America, in Southeast Asia, and even in China.” And Tezuka also wrote: “My experience convinces me that comics, regardless of what language they are printed in, are an important form of expression that crosses all national and cultural boundaries, that comics are great fun, and that they can further peace and goodwill among nations. Humor in comics can be refined and intellectual, and it has the power to raise the level of all people’s understanding.”

Again, thank you very much for this lovely award.

--Back to top--